Drama On The Nile: Major Developments in Sudan and South Sudan

A turning point may have been reached in the civil war in Sudan. At the same time, the risk of a new armed conflict is rising in the world’s youngest country, South Sudan

The civil war in Sudan is nearing a grim milestone. The armed conflict in Africa’s third-largest country has, as of April, raged for two years, resulting in over 8.8 million internally displaced people and 3.5 million refugees abroad. Over half—approximately 53%—of the internally displaced are reportedly children under the age of 18.

In the area around the capital, Khartoum, which has otherwise always been known as an oasis of peace in a war-torn country, more than 60,000 people have lost their lives. Due to the ongoing conflict and the chaos it has brought, there has been no systematic monitoring of the war’s victims. Several analysts and international organizations speak of a colossal number of unreported deaths and destruction in provinces and states outside of Khartoum, with the western Darfur region said to be particularly hard hit. Famine and otherwise preventable diseases have worsened the war’s consequences. Numerous reports also state that rape is being used extensively as a weapon by all parties in the conflict.

Read our latest analysis on the new ‘small and beautiful’ doctrine of China’s BRI by our Asia Editor, Gabriel Lane.

The civil war in Sudan, which has at times been called “the forgotten war”, overshadowed by events in Gaza and Ukraine, broke out as a result of internal power struggles between Sudan’s two “strongmen.” Following the Sudanese Revolution in 2018 and the subsequent military coup in 2019, the country’s dictator Omar al-Bashir— who had ruled the country with an iron fist for roughly 30 years —was overthrown. Initial optimism was quickly replaced by concern, as General Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, head of Sudan’s armed forces (SAF), seized power in a 2021 coup. The opposing faction, headed by Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo (known as Hemedti), leads the paramilitary group Rapid Support Forces (RSF), which has its origins in the camel-riding, fearsome Janjaweed militias that al-Bashir used in the 2000s to crush rebellions, commit ethnic cleansing, and spread terror in the Darfur province. The 2021 military coup was initially supported by Hemedti and the RSF, but fears of centralization led the RSF to attack SAF bases across Sudan on April 15, 2023, where they at the same time managed to seize the capital, Khartoum. And just like that, the civil war had begun.

Until recently, the war had reached a relative stalemate, but with a major offensive toward Khartoum, the SAF has succeeded in recapturing the country’s presidential palace. Symbolic as the victory may be, the SAF’s progress could signal a turning point in the war. This viewpoint is further supported by the fact that al-Burhan has been especially effective in securing support from both Russia and Iran. Iranian drones and Russian weapons have been crucial in securing SAF’s successes on the battlefield, and Russia has even recently secured a promise for a naval base in Port Sudan on the Red Sea coast.

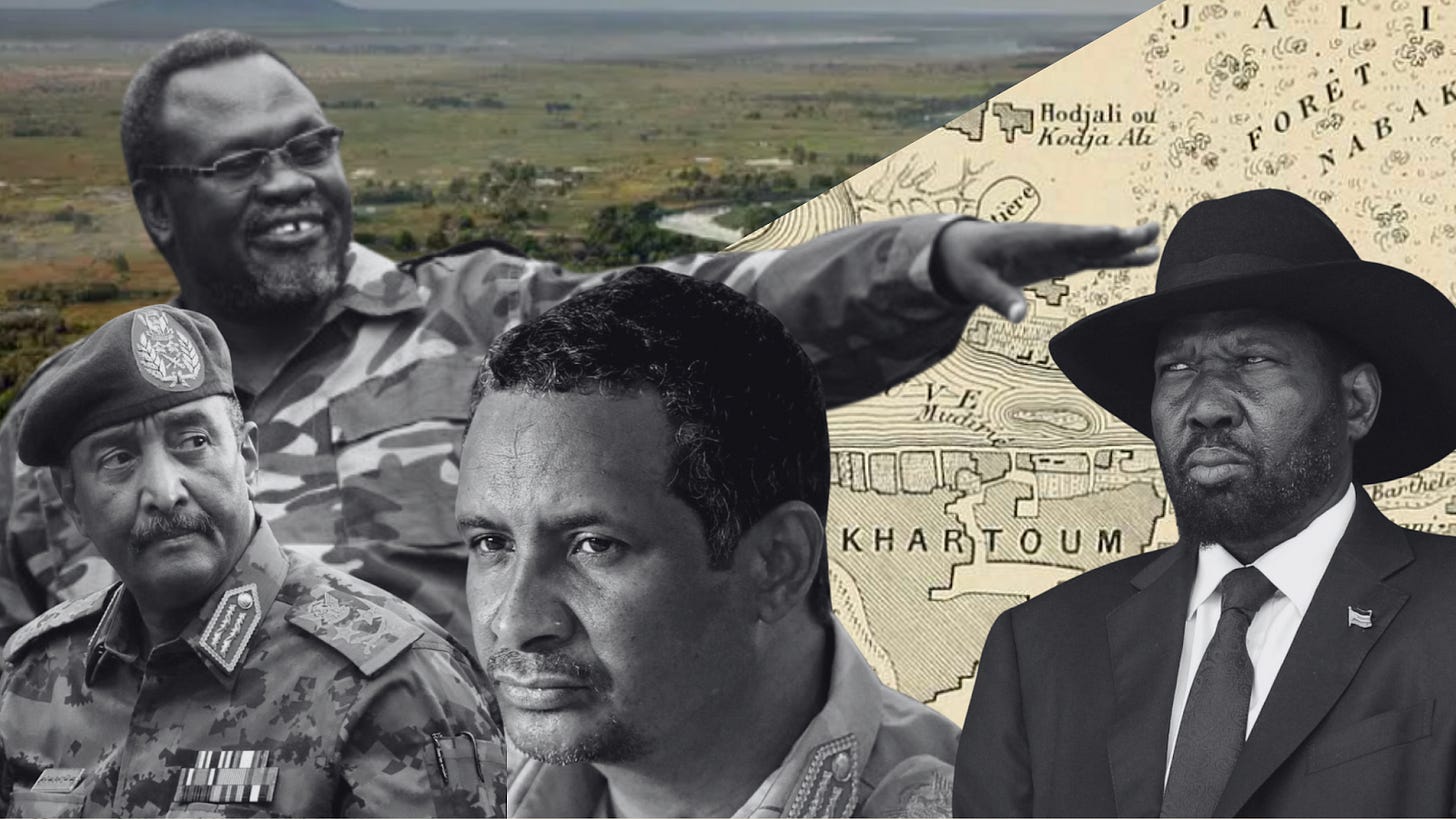

From left: General Al-Burhan (head of Sudan’s army and de facto leader of the country), Riek Machar (First Vice President of South Sudan), Hemedti (leader of the paramilitary group, Rapid Support Forces), Salva Kiir (President of South Sudan). Source of photos: AP

Trouble Brewing to the South

Meanwhile, the war now threatens to spill over into the country’s southern neighbor, the world’s youngest country, South Sudan. Both SAF and RSF support their respective militias in the neighboring state. This comes at a delicate time for South Sudan. Political tensions and storm clouds are currently gathering over the capital, Juba. The UN’s Special Representative for South Sudan, Nicholas Haysom, briefed journalists on March 24, warning that unless drastic measures are taken, there is a high risk of a full-scale civil war breaking out in the country on the banks of the Nile. At the center of the new tensions are South Sudan’s enigmatic cowboy-hat-wearing President Salva Kiir and First Vice President Riek Machar.

The oil-rich country has only just barely emerged from the grips of war. Kiir and Machar are both parties to a fragile 2018 peace agreement, which ended a five-year civil war between forces mobilized along tribal lines loyal to either Kiir or Machar, and during which up to 400,000 people lost their lives. The peace deal remains fragile, largely because each leader still de facto controls their respective half of the country’s armed forces, geographically dispersed across the nation.

The new tensions arose when Kiir dismissed several key government officials in February as part of a cabinet reshuffle, dismissals seen by Machar’s faction as a breach of the 2018 peace agreement. As a result, sporadic bloodshed broke out in the north of the country, after which Kiir deployed loyal forces to the region, backed by airstrikes. Images shared on social media show women and children with horrific burn marks, and an investigation by independent Sudan Post found that ethyl acetate, an extremely flammable chemical, was likely used in the attack. More than 60,000 civilians have fled as a result of the recent violence. During the fighting, a UN helicopter deployed to evacuate UN troops from the area came under heavy fire, killing one UN crew member and a South Sudanese general. The UN-affiliated Radio Miraya reported that the so-called White Army, linked to Machar, is suspected of being behind the attack. Countries including France, Canada, the Netherlands, Germany, and Norway have condemned the attack, and the U.S. Embassy has gone so far as to evacuate all non-essential American personnel from the country.

Last week, the situation took a dramatic turn when Machar was arrested by Kiir’s forces and accused of inciting rebellion. Machar’s party, Sudan People’s Liberation Movement-In Opposition (SPLM-IO), issued a press release implying that the arrest warrant for Machar “in effect” renders the 2018 peace agreement void. This is a significant step toward further escalation.

The growing conflict is on the agenda of the regional IGO, the Intergovernmental Authority on Development (IGAD). IGAD, which has a mandate to act on peace and security matters in South Sudan, met on March 12 for a summit to discuss the situation. Likewise, Kenya, currently holding the presidency of the other important regional bloc, the East African Community, has sent the country’s former Prime Minister, Raila Odinga, to South Sudan with a mission to de-escalate the situation. Odinga met with Kiir and urged South Sudan’s prime minister to reach a peaceful resolution. However, he was denied a meeting with the detained Machar.

Leading IGAD member Uganda has already, as of mid-March, sent its own special forces to South Sudan to secure Juba, the capital. Uganda’s move is, however, seen as controversial, as President Museveni is a close ally of President Kiir, and the action could be perceived by Machar’s supporters as a further provocation.

The hope for a peaceful resolution to the conflict could lie with the country’s youth and in a possible swift intervention by the international community. South Sudanese-American political scientist Abiol Lual Deng points to the fact that the young South Sudanese population—around 66% of whom were under the age of 24 in 2021—does not share the same mindset of ethnic division as the country’s leaders. She is also hopeful that the international community will step in should the budding conflict escalate into a full-scale war, noting that increased regional instability is not in the interest of any partners in the region.